It worked in Portugal—why not in Portland?

Sixty percent of Oregonians agreed on Election Day 2020, and in 2021, drug decriminalization became a reality in the state.

Now, three years later, Oregon legislators voted to recriminalize the possession of illegal drugs. On April 1, Governor Tina Kotek signed it into law, and on Saturday, August 31—Overdose Awareness Day—the grand experiment in the decriminalization of drug possession—the first such measure ever undertaken in this country—breathed its last.

What happened?

For one thing, the state’s substance abuse treatment system, already ranked last in the US, became even more threadbare during the pandemic. And for another, barely 1 percent of offenders opted for rehabilitation.

Taking the two factors above into account, is it any surprise that a total of 85 out of 7,227 people cited statewide actually did the substance abuse program?

Is it any surprise that the conviction rate for people with citations was an astronomical 89 percent—not because they were found guilty at a hearing or trial but because, in most cases, they didn’t bother to show up?

Is it any surprise that in Measure 110’s brief life, Oregon circuit courts imposed $899,413 in fines on people cited and convicted, but collected just $78,143 or less than 10 percent?

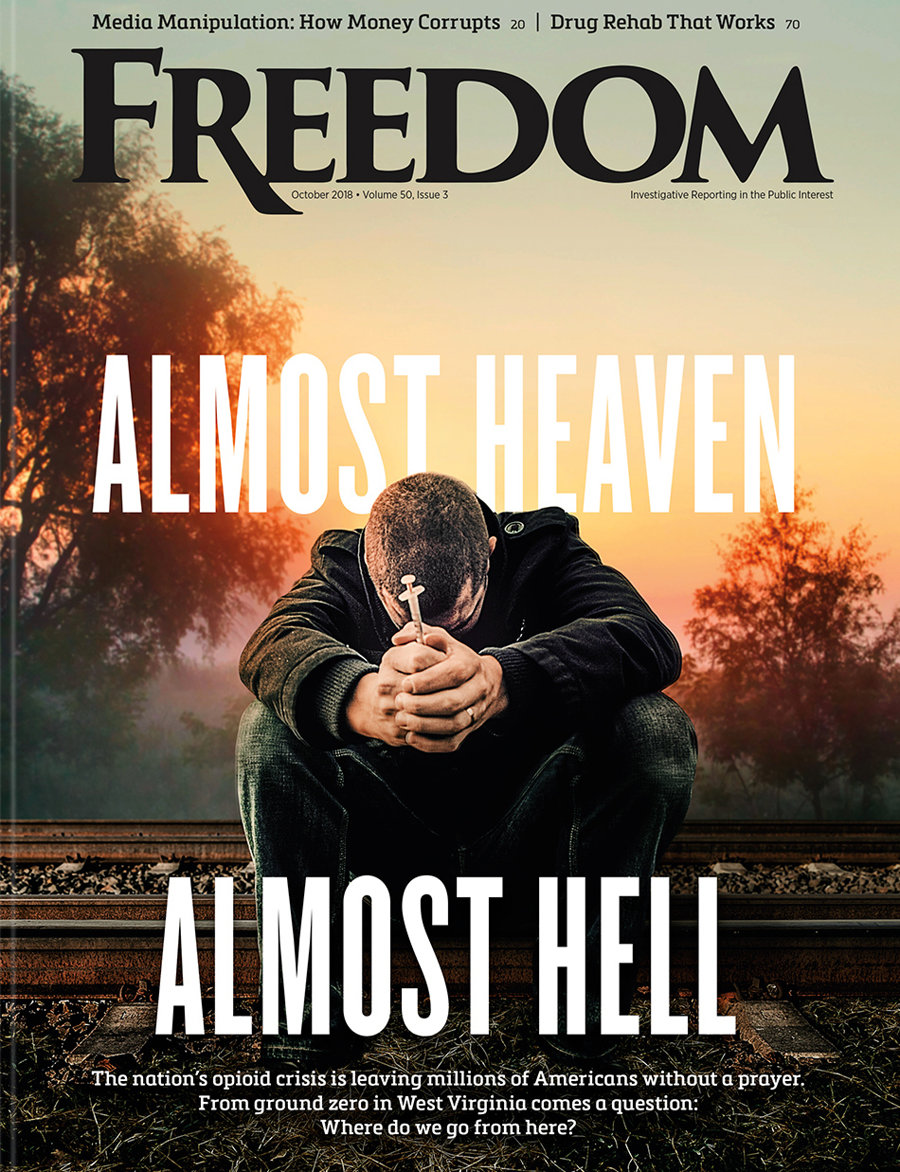

Meanwhile, drug abuse in Oregon has continued to skyrocket. Fentanyl overdoses reached such a deadly peak that state and local leaders declared a 90-day state of emergency in downtown Portland in January.

Those who say the measure should be given another chance argue that all it would take is a few adjustments to fix it. It should be more like Portugal’s, they say. There, offenders aren’t invited to seek treatment voluntarily but are instead pushed by “dissuasion commissions” to do so.

Criminalization didn’t work. Decriminalization didn’t work. Wouldn’t it make more sense to try something different?

Don’t blame your soaring drug abuse on Measure 110, proclaims the American Medical Association’s monthly journal. There is no link, they say, between climbing fentanyl mortality rates and decriminalization.

Doubtless, there will be more weighing in from more talking heads and more head-scratching over a viable solution to Oregon’s out-of-control drug problem. The state is number two in the country in substance abuse. So critics of “recriminalization” ask the inevitable question: If criminalizing possession was ineffective enough to go hunting for a better solution in the first place, how does recriminalizing it now suddenly become the best solution? You tried that before and failed, so you should try it again, and somehow you’ll get a different, better result this time?

Wasn’t it Einstein who never said that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results?

Criminalization didn’t work. Decriminalization didn’t work. Wouldn’t it make more sense to try something different? Say, something with a successful record of results? Something that pulls the drug problem out by the roots—rather than waiting until abusers have already abused and offenders have long since offended?

Try something effective. Start with youth. Start in schools. Start with people at the community level who’ve been scarred already by their loved one’s drug abuse. These are the people who’ve lost the most and have the greatest motivation to prevent others from so losing.

Lance Dyer lost his 14-year-old son—a bright and popular honors student and defensive end on the school football team—to suicide, a byproduct of dangerous synthetic drugs. Dyer decided to fight the forces that killed his son.

Against impossible odds, Dyer and his volunteers attacked harmful drugs at the grassroots level through education.

“I didn’t go looking for this fight,” he said. “It came to my front door. It kicked my front door down and it came in on my son. They brought it to me. Just like it was brought to the other parents across the country. And several of us decided to fight back. And this is how we fight back: We try to educate young people. We try to educate the adults. We try to partner with organizations that want to make a difference.”

After several false starts, he found the most effective tools were the Truth About Drugs materials of Foundation for a Drug-Free World, which, in addition to booklets on every drug of choice, include 16 PSAs and a feature-length documentary in which former addicts share their personal stories.

“The Truth About Drugs material is done in a way that a young person—a young adult, high-school kid—can understand it. They get it. And they happen to see one of the videos, they hear from their peers. It’s not Nancy Reagan or the DEA or even a Lance Dyer saying, ‘Don’t do drugs.’ This is coming from people that they understand: their peers. They get it.”

Dyer’s successes with the Truth About Drugs—as confirmed by an avalanche of testimonials from parents, teachers and ex-users—are multiplied ten-thousandfold on the global scale. Through a worldwide network of volunteers, 50 million drug prevention booklets have been distributed, tens of thousands of drug awareness events have been held in some 180 countries and Truth About Drugs PSAs have aired on over 500 television stations. Result: Millions now know—really know—the destructive side effects of drugs and can intelligently, without coercion, weeping or threats, make the decision for themselves not to use them.

So, Oregon, we know you’re serious about your drug problem. You were the first to decriminalize drug possession. It was flawed but sprang from an impulse to address the problem. Had it worked, you would have been hailed the leader in curbing substance abuse. But it didn’t. Let’s move on.

Your Secretary of State, Shemia Fagan, who originally voted for Measure 110, has a brother who suffered the torture of drug abuse.

Last year, lamenting the failure of decriminalization, Fagan said, “When Oregonians passed Measure 110, we expected that our loved ones battling addiction would have access to treatment and a chance for a better life.

“We expected there [would] be fewer of our neighbors struggling on the streets,” she said.

Shemia Fagan and her family are but one pixel on a football field-sized photograph of those afflicted by a scourge that doesn’t care how sincere you are, what your political affiliation is or whether you’re a ditchdigger or a Secretary of State.

How about thinking outside the criminalization-decriminalization box, Oregon? How about taking it to the streets, the schools and the communities—with education at the grassroots level?

“Make no mistake, this is a matter of life and death,” Fagan said.

Yes, it is.