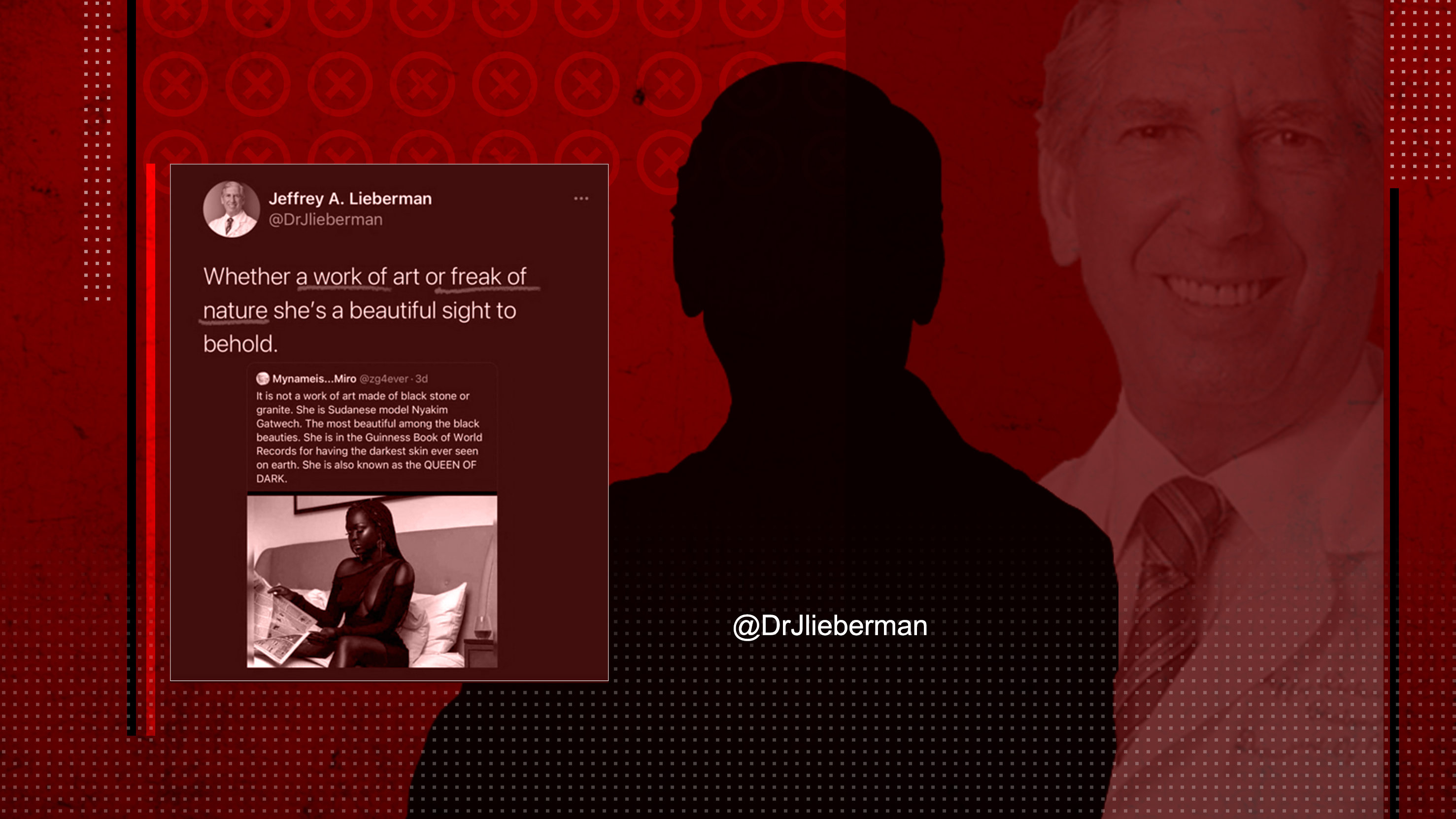

Such was the case when Lieberman posted denigrating and racist comments on Twitter about Nyakim Gatwech, the Ethiopian-born model of South Sudanese descent internationally known as “Queen of the Dark” for her ebony skin and stunning appearance.

In a flagrant display of bigotry, Lieberman described Gatwech as a “freak of nature,” generating outrage from Gatwech’s fans and some of Lieberman’s peers. Columbia University suspended him from his chairmanship post, and the New York Office of Mental Health demanded his resignation as executive director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

“We condemn the racism and sexism reflected in Dr. Lieberman’s tweet,” said Thomas Smith, who replaced him as director of the Institute after Lieberman immediately stepped down.

Columbia professor of psychiatry Robert Klitzman told the New York Times the incident “really highlights how deep and pervasive some of our own unconscious biases can be.”

Pervasive is an accurate description, but certainly psychiatry’s racial biases are not “unconscious.” They are endemic, well established, and rooted in a history of elitism.

Beginning in 1792, Benjamin Rush, icon of the American Psychiatric Association extolled as the “father of American psychiatry,” declared that Blacks suffered from a “disease” he called Negritude, theorizing that it derived from leprosy. According to Rush, “Like lepers, they needed to be segregated for their own good and to prevent their infecting others.”

Afflicted individuals were “cured” once their skin turned white.

Individuals of African descent had a much higher pain threshold than whites, a “pathological insensibility,” according to Rush, that existed because they had evolved physiologically under the conditions of slavery. Rush’s dehumanizing profile did not end there.

In 1851, Dr. Samuel A. Cartwright, a Rush apprentice, invented the mental disorder drapetomania to classify what produced runaway slaves. Drapetes, meaning “runaway slave,” was coupled with mania, meaning crazy. He also coined the term dyasethesia aethiopis—a diagnosis of laziness with impaired sensation. Cartwright asserted that drapetomania caused slaves to have the “uncontrollable urge” to escape from their masters and “In noticing a disease not heretofore classed among the long list of maladies that man is subject to, it was necessary to have a new term to express it. The cause in most cases that induces the negro to run away from service, is as much a disease of the mind as any other species of mental alienation, and much more curable, as a general rule,” he wrote.

The “cure” was “whipping the devil out of them” and was justified in medical terms contending that flogging made idle slaves “take active exercise” that vitalized blood to their brain “to give liberty to the mind.”

A Leading Light

More than 200 years later, that bigoted mindset has permeated the entire psychiatric profession, as evidenced by the broad acceptance Lieberman had enjoyed within the psychiatric community before being caught out on Twitter. Characterized as a leading light of the mental health industry, Lieberman published some 700 articles and 17 books, including textbooks, and was considered an international expert. From May 2013 to May 2014, he was president of the American Psychiatric Association.

Though a few psychiatrists spoke out against Lieberman, one organization remained utterly blind to his biases.

One day after the New York Times story, the Spanish Society of Psychiatry (SEP) published an article describing a favorable judgment the organization had obtained against Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR) Spain and CCHR International for distributing publications that “violated the right of honor of all psychiatrists.”

The oxymoronic nature of the article should have been evident to anyone familiar with psychiatry’s long history of abuse. The words “honor” and “psychiatry” have never belonged in the same sentence in any characterization.

Since 1968, CCHR and individual Scientologists have been documenting psychiatric abuses, including psychiatric racism. CCHR and Freedom Magazine, published by the Church of Scientology, were the first to expose psychiatric slave camps in South Africa, where Blacks were forced into slave labor.

The Freedom exposé led to a World Health Organization investigation into the camps and a 1983 report: “Although psychiatry is expected to be a medical discipline which deals with the human being as a whole, in no other medical field in South Africa is the contempt of the person, cultivated by racism, more concisely portrayed than in psychiatry.”

Those would not be the final words from WHO on psychiatry. In June 2021, WHO published a damning 200-page report on psychiatry’s coercive practices including involuntary treatment, electroshock and psychosurgery, reinforcing concerns over the failures, and abuses, of the mental health system globally.

By the time that report was published, CCHR had been documenting and exposing psychiatric abuses for more than half a century.

Mea Culpa

In January 2021, the American Psychiatric Association finally admitted its complicity in helping sustain the racism that was by then part of the fabric of psychiatry, conceding that it had enabled “discriminatory and prejudicial actions” and “racist practices in psychiatric treatment.”

The APA promised to make amends for its behavior by providing better quality psychiatric care for people of color. But after hearing racist statements from one of its own luminaries, a year after this mea culpa, makes that promise ring hollow.

Psychiatry is not a helping profession. It is a tool for control that enables its practitioners to victimize anyone they consider inferior. And in psychiatry’s view, that’s nearly everyone.

Jeffrey Lieberman’s racist views should not be brushed off as just one man’s bias. They are embedded in the psychiatric industry’s fundamental world view.

And until that is evident to everyone, CCHR and Scientologists will continue to expose and speak out against psychiatric abuse in all its forms.