The Corruption of Information

This commentary from a leading media analyst and author is the second in Freedom’s Media & Ethics series, a regular forum presenting diverse views on media as a cornerstone of a robust democracy. The series explores what’s wrong with media today and, equally important, what can be done to change it.

At the time of Watergate, Americans trusted the news media. Today, if it were not for Congress, the media would rank as our least-trusted institution. A recent Gallup Poll found that less than one in four Americans say they “trust” the news media—newspapers and television news alike.

The media’s confidence crisis owes in part to what a Carnegie Corp. report called “the spread of the entertainment virus.” A theatrical style of news has emerged that is designed to compete with entertainment media for readers’ and viewers’ attention. News reports that feature celebrities and dramatic incidents have doubled since the 1970s, now accounting for more than a third of news coverage. What Pulitzer Prize recipient Alex Jones calls “the iron core” of news—the news that aims “to hold government and those with power accountable”—has shrunk dramatically.

The level of tabloidization is sometimes stupefying. In 2011, CNN and its sister station HLN carried more than 500 stories on Casey Anthony’s Florida murder trial. CNN even erected a temporary two-story air-conditioned structure across from the courthouse so that its crews could work in comfort. Earlier this year, CNN topped that effort with its all-out coverage of the disappearance of Malaysian Airlines Flight 370. If the early days of that tragedy were imminently newsworthy, CNN found a way to stretch the story into weeks, luring its viewers with repeated promises of “breaking news” that turned out to be anything but new developments and everything but news.

News organizations blame the audience for tabloidization, saying that readers and viewers are addicted, as a CNN anchor put it, to “America’s newest guilty pleasure.” Television ratings do in fact jump when a riveting crime or scandal occurs. Over the long term, however, such stories dull Americans’ appetite for more substantial news. A 2013 Pew Research Center survey found that a third of American adults—and an even greater number of the well-educated—had abandoned a once-trusted news source, saying that it “no longer provided them with the news they were accustomed to getting.”

Shallow news has weakened Americans’ grasp on public affairs. Over the past three decades, despite a rise in Americans’ education level, their knowledge of politics has slipped. Worse, their level of misinformation has risen. As one observer said recently, the news media are making us “dumb.”

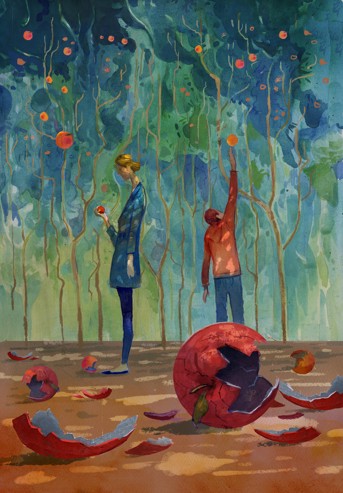

We need news organizations to help us understand the world of public affairs beyond our direct experience. Yet, as journalist Walter Lippmann noted, democracy falters “if there is no steady supply of trustworthy and relevant news.” To be sure, citizens bear some of the responsibility for the declining quality of news. In the final analysis, though, they suffer from a news system gone haywire. They are told they are in Kansas but are being led through Oz.

A solution might exist in the continuing fragmentation of the news system. When traditional news outlets first faced audience competition from cable and Internet outlets, they responded with tabloidization. As the fragmentation has continued, however, they are finding that Americans prefer outlets that focus on news of a particular type. For some, that’s a partisan outlet such as Fox or MSNBC. For others, that’s a traditional outlet such as NPR or the New York Times.

The emerging era of “the niche audience” is not, however, a substitute for the now bygone era when the vast majority of Americans got their news from a trusted source. One of today’s niche audiences is the infotainment audience—those Americans that revel in exotic content. Another of today’s niche audiences is a non-audience. The same media system that gives people a wide variety of news options also makes it easier for them to avoid news altogether. About a fourth of Americans—and a much higher proportion of young adults—fall into this category.

Our democracy will survive Americans’ flight from real news but it will not thrive. It is impossible to have informed opinion and sensible debate when large numbers of citizens, because of their own failings or those of the media, are out of touch with the realities of our time.

Thomas E. Patterson is Bradlee Professor of Government and the Press and teaches at the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. His latest book, Informing the News: The Need for Knowledge-Based Journalism, examines the causes and consequences of declining news quality and what news organizations and journalists can do to reverse the trend.