Challenges for Change in Cameroon

A land of contrast and promise, of violence and struggle, Cameroon is a fragile young democracy with deep tribal roots, a nation whose rich natural resources portend a bright future.

But its 20 million people face challenges that include diseases such as cholera, a high rate of illiteracy, floods of refugees from turmoil in neighboring nations, and an array of human rights issues that have long plagued many sub-Saharan nations.

Beginning more than a decade ago, teams of volunteers from Youth for Human Rights International undertook a series of extended visits to many of the countries of West and Central Africa to introduce and establish broad-based human rights educational programs. Their purpose: to bring about awareness of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and, most importantly, to encourage individuals to undertake actions that would make those rights more relevant to local needs, more effective, and more forceful.

Focusing on youth, the programs gained momentum from 2004 onward, expanding in the nations of Ghana, Liberia and Sierra Leone. Human rights clubs were established in high schools, empowering young people as researchers and advocates, with teams of students turning their attention on local and regional human rights problems and their solutions.

The thrust of the educational efforts was to select a particular human rights issue such as child trafficking, lack of education, or religious intolerance, to document the problem, and to advocate for its resolution. Sierra Leone students, for example, investigated and reported on rape victims, amputees and child soldiers impacted by that nation’s 11-year civil war.

Instruction on film and photography was included, with teams encouraged to produce videos as part of their campaigns. By means of these youth-driven public awareness efforts, the students involved—who now could genuinely be referred to as human rights activists—reached more than 12,000 of their peers in schools, community groups and other gatherings. Some even trod on broader stages, presenting their messages about the importance of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to hundreds of thousands or even millions through national media.

The programs spread to Togo, then to Ethiopia and, in 2012, to Cameroon.

The director of the program in Cameroon, Bertrand Tientcheu, had been working as a Christian missionary at the World Council of Churches office in West Africa when he met representatives of Youth for Human Rights International who were then in the midst of a multi-nation educational tour to promote awareness and utilization of the Universal Declaration.

Tientcheu struck up enduring friendships with those on the tour, including Joseph Yarsiah, then the director of Youth for Human Rights Liberia.

Yarsiah knew full well the importance of human rights because he had twice experienced the horrors of being a war refugee. In 1990, he and his family fled Liberia for Sierra Leone. After returning to Liberia, they were forced to leave again, escaping in 1995 with some 5,000 others on a boat designed to hold 1,000—and with no food or water. He spent the next several years in Ghana, returning home once again in the late 1990s.

Yarsiah, who went on to become a Youth for Human Rights International program director for Africa, is now studying for his master’s degree at the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution at George Mason University. Reflecting on the carnage that claimed hundreds of thousands of lives in Liberia, he says, “I realized that the reason behind all of this was just major human rights abuses…. It was important to get involved, whatever contribution I could make, to help bring [human rights] to my country.”

Tientcheu, born in 1975 in Cameroon’s largest city, Douala, had been interested in human rights from an early age.

“I read a lot about Dr. Martin Luther King, who was a pastor and also an activist for justice. His engagement and his passion to defend human dignity inspired me,” says Tientcheu, commenting on his experiences in an interview with Freedom.

Another influence was Mahatma Gandhi. “I watched many films, many documentaries about him, his sense of integrity and also his passion, the way he fought for the freedom of India,” says Tientcheu.

His own humanitarian work started in 1995, educating people about HIV and AIDS. After seeing the scope and impact of the Youth for Human Rights educational initiative, Tientcheu took on the task of informing his compatriots about their inherent rights, becoming director of Youth for Human Rights Cameroon in 2012. In 2012, Dr. Mary Shuttleworth, president of Youth for Human Rights International, visited Cameroon and with Tientcheu met with Dr. Chemuta Divine Banda, chairman of Cameroon’s National Commission on Human Rights and Freedom (NCHRF) and General Marie Abunaw Nana, technical adviser to the Ministry of Justice. The following year a memorandum of understanding was signed with the NCHRF.

According to the memorandum, NCHRF and Youth for Human Rights International agreed “to collaborate, develop and propose pilot curricula and one or more courses of study in human rights and Human Rights Education (HRE).” Similar agreements have been established with authorities in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Togo and Ethiopia.

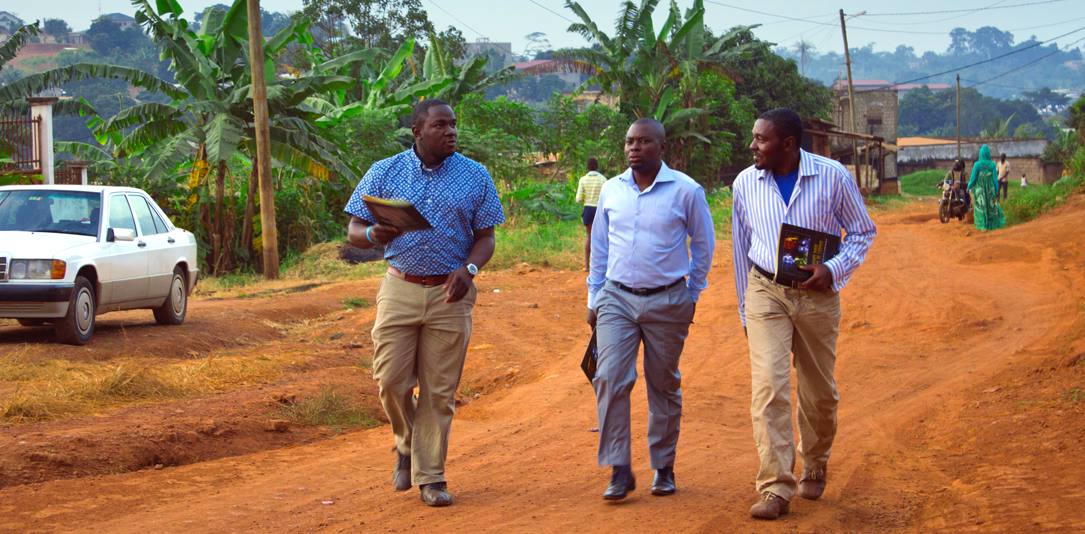

Today Tientcheu and his co-workers at Youth for Human Rights Cameroon deliver lectures and classes to youth and adults alike at schools, churches and other venues on the importance of human rights and the power of education, on occasion teaming up with others, including faith-based organizations comprised of members of various Christian and Muslim groups.

Attorney Timothy Bowles, who has undertaken many extended visits to West and Central Africa to establish educational programs on behalf of Youth for Human Rights International, points to an additional dimension: “In my view, the greatest challenge facing Africa, including Cameroon, is literacy, guaranteed by Article 26 of the Universal Declaration.” It has been estimated that only 78 percent of males and 65 percent of females age 15 and over in Cameroon can read and write.

But Bertrand Tientcheu knows the many challenges his nation faces and remains undaunted. “Working in the area of human rights for me has been … a journey of discovery, discovering myself as not just a spiritual person but also discovering human beings as spiritual people, as spiritual beings,” he says.

Tientcheu notes that the multimedia educational campaign, which has already touched the lives of thousands in Cameroon, created a positive impact over the past year. He looks to continue the campaign with an emphasis on strengthening the public’s awareness of their responsibilities within a democracy, knowing that with freedom comes many privileges but even more responsibility.

“Though Cameroon has ratified several international human rights instruments, like the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, still we have the serious problem of implementing those rights,” he says.

As part of the ongoing educational effort, in August 2014 Tientcheu met with the King of Bafut at his palace. The most powerful of the ancestral kingdoms located in the area of Cameroon known as the Western Grassfields, Bafut is a region where the hierarchy that has ruled for centuries remains in place. But Tientcheu’s visit was a case of the old welcoming the new: the king and his delegation were eager to learn about the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in order to implement them in Bafut youth programs.

Speaking from his own experiences in helping to train hundreds of young men and women as human rights advocates, Joseph Yarsiah says, “When young people confront other young people about human rights issues, it motivates them to take a stand and get activated. I’ve seen great change in their lives. I’ve seen how much they’ve been inspired.”