Her Name Was Silje

Turning 18 for most young people is an exciting time, marking one’s entry into adulthood as hopes and aspirations for the future seem ripe for the taking. But for Silje Owre of Norway, that was not the case.

According to her father, Silje was worried about reaching this milestone age because it meant she would have to transition into the nation’s adult mental health care system. She had heard things about adult psychiatry’s unbridled reliance on powerful psychopharmaceuticals to “treat” emotional or psychological problems and to administer psychiatric drugs when the physical sources of a person’s problems were either undiagnosed or not properly addressed with actual physical handlings.

Diagnosed in 2006 at age 14 with chronic fatigue syndrome, as well as a lesion in a part of the brain responsible for emotions, the once active, vivacious child suddenly became bedridden and at times even unable to feed herself without assistance. This went on for the next two years, until her physical and mental health started to improve. Silje’s dad, Espen Owre, 46, attributed her turnaround to the kind of help she received from a team of pediatric specialists.

“The youth team at [Akershus University Hospital] did not give Silje any kind of medication but [instead gave] cognitive training,” he said in an email to Freedom. “Instead of being locked in a depressing institution, Silje was during that period staying home, and a team came to our home, including us parents and our son. They took Silje out [for coffee] and shopping, creating a good and stable environment for her. … They treated her with love and understanding.”

Tragically, however, Silje’s concerns about adult mental health care in Norway eventually proved morbidly valid. On November 5, 2012, after two years of being heavily dosed with a slew of prescription antidepressants, antipsychotics, painkillers and tranquilizers, Silje was found dead, along with a suicide note, of a heroin overdose in an Oslo hotel room. Compounding her family’s despair, Silje was supposed to have been receiving closely monitored care as an inpatient at the drug detox ward at Akershus University Hospital, which in Norwegian is abbreviated as “Ahus.”

Not long after undergoing surgery in fall 2011 to remove a cystic brain tumor described as being small and benign, Silje survived a suicide attempt on New Year’s Eve after jumping off a bridge that stood more than 20 feet above a highway. She suffered multiple bone fractures and spent three months at Sunnaas Rehabilitation Hospital.

As she consistently struggled with bouts of depression and emotional instability, a report shows that between 2010 and 2012 Silje had multiple “episodes of self-harm” such as “severe cuts in the wrist for suicide and serious suicide attempts with drugs” that included an August 2010 trip to the emergency room after a prescription pill overdose. Nonetheless, on the day of her fatal heroin binge, the ward’s supervisors—psychologist Knut Erik Duna and his boss, psychiatrist Geir Ebbestad—gave Silje a day pass, ostensibly to attend school.

The report explains the rationale for this fateful decision with a statement attributed to Duna dated three months after Silje’s death. “With chronic elevated suicide risk it is always such that suicidal thoughts vary from week to week, from day to day, and sometimes from hour to hour,” Duna wrote. “We have of course never intended or claimed that this patient was cured of her chronically elevated suicide risk. She was granted leave because we assessed that she was not acutely suicidal.”

Silje, according to a report, had told a psychologist that she “will … take her life with an overdose of heroin. She does not want to live like a junkie and does not want to live without heroin.”

And that’s what happened. The report of the County Governor—the King’s and Norwegian government’s representative in each of the nation’s 18 counties—indicates that Silje never showed up at school on November 5, and the school had not been notified that she would come that day. “The complainant [Espen Owre] also writes that they were greeted ‘by a wall of silence’ when they made contact with the department to clarify whether the patient was in the department.”

The day after Silje failed to return to the hospital as scheduled, her mother called the ward and wasn’t “informed that the patient had not come back after leave the day before,” according to the report.

Silje was reported missing to the police on November 6. “Police and a priest came to their home about an hour later stating that their daughter was found dead,” the County Governor’s report stated. Silje’s mother, Lise, ended up being the one who informed the hospital that Silje had committed suicide.

Espen Owre’s grief soon shifted to outrage aimed at what he saw as a dysfunctional mental health system. Owre filed a complaint against the hospital with the medical oversight office, and he and Lise took to the airwaves as the national news media flocked to the story.

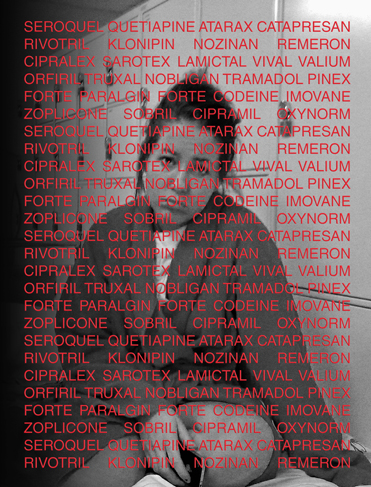

On the Facebook page he established for the Silje Benedikte Foundation, which spreads the word about the dangers of psychopharmaceuticals and advocates for reforming Norwegian mental health care, Owre posted a list of the drugs prescribed to his daughter between 2010 and 2012. According to her father’s research into Silje’s prescription history, she consumed a combined total of more than 10,000 doses of the following:

- Seroquel/Quetiapine

- Catapresan

- Rivotril/Klonipin

- Nozinan

- Remeron

- Cipralex

- Sarotex

- Lamictal

- Vival/Valium

- Orfiril

- Truxal

- Nobligan/Tramadol

- Pinex Forte/Paralgin Forte/Codeine

- Imovane/Zopiclone

- Atarax

- Sobril

- Cipramil

- OxyNorm

Eight of these medications—Seroquel/Quetiapine, Remeron, Cipralex, Sarotex, Lamictal, Nobligan/Tramadol, Imovane and Cipramil—are known to increase suicide risk, especially for children and young adults.

The European Medicines Agency’s scientific committee, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use, reviewed the use of antidepressants in children and adolescents in 2005, and concluded that suicide attempts and suicidal thoughts were more frequently observed in clinical trials among children and adolescents treated with certain classes of antidepressants. Both Cipramil and Cipralex fall into this category of drugs.

After a year and a half of a heated back-and-forth between the findings of the government medical experts, Oyvind Watne and Tor Ketil Larsen—who exonerated the hospital and its staff from any wrongdoing—and the Owres’ detailed rebuttals, an unprecedented outcome occurred.

In his official response to the investigation, Petter Schou, the county’s chief medical officer, overruled the experts and confirmed the Owres’ charges of malfeasance by Ahus staff. “We do not find recorded justifications for the drug treatment given, neither for actual medication nor possible medication,” states a key finding of Schou’s report. “The County Governor’s assessment is that the treatment the patient received, including the drug treatment, was not in accordance with proper practice.”

This garnered quite a bit of press, which eventually led to Ebbestad losing his job and Ahus administrator Trond Rangnes’ public apology to the Owres. “Silje had been misdiagnosed,” said Espen Owre as he recounted the report’s findings. “She received indefensible medication, she was mistreated, it was bad evaluation, sloppiness in the records, poor [suicide] prevention, lack of notification procedures and lack of contact with relatives.”

The Citizens Commission on Human Rights, co-founded in 1969 by the Church of Scientology and noted author Dr. Thomas Szasz, has long been a vocal critic of psychiatric human rights abuses. “Silje’s story is unfortunately far from unique,” said a spokesperson for CCHR Norway via email. “What is very unique, however, is that parents take on the battle the way they have done, to confront the system and to take action both to get justice for Silje and to prevent others from suffering a similar fate.”

In September 2013, activist Hans-Erik Husby joined Espen Owre at the front of a protest march that brought demands for reforming the mental health system to the steps of Parliament. Formerly known as “Hank von Hell,“ lead singer of the raucous rock band Turbonegro, Husby detailed his own experience with Norwegian mental health care as a recovered drug addict who went through mainstream rehab regimens that utilize psychotropic drugs. “I discovered that there are alternatives to handling man’s problems in life, rather than just drugging or using brute force to make man ‘behave,’“ he said in an email to Freedom.

Calling for “drug-free residential units,” CCHR Norway stated that the foundation for such facilities must include “a safe place to be, a bed to sleep in, regular meals and people to talk to.”

Husby pointed out methods that he said have shown promise as viable alternatives to psychotropic drugs. “By helping people communicate to better sort out the practical problems in their lives … much can be done in order to repair a broken mind,” Husby said. “Making people realize that they actually can take responsibility in their lives also seems to have helped many individuals out of … hopelessness.”

Largely as a result of CCHR and the Owre family’s activism, there were indications of government action toward shifting mental health care away from its dependency on drugs. By the latter part of 2014 the Parliament’s Health Committee Chairwoman Kari Kjos and national Health Minister Bent Hoie had called for drug-free treatment options. Kjos also authored a bill that prohibits primary care doctors from prescribing antidepressants to patients younger than 25.

In December, Norway’s most populous health care region, which includes Oslo, directed doctors and staff members to implement measures aimed at improving access to drug-free treatment as well as improving the documentation of psychotropic drug prescriptions and side effects. Additionally, the Hamar region became the first health care sector to roll out a model for drug-free mental health care.

As a key starting point for effecting change in the mental health system, Espen Owre noted the simple efficacy of placing greater emphasis on compassion and communication instead of the guesswork-style prescription practices that dominate contemporary psychiatry, coupled with the wall of patient confidentiality that shuts loved ones out of the healing process.

Comparing the atmosphere at Sunnaas Hospital with the detox psych ward at Ahus, Owre said: “They respected Silje, they talked to her, gave her love and understanding. Let me give you an example: When Silje was admitted to Sunnaas, the staff could say to her, ‘Hi, I heard that your parents are coming to visit you today, let’s go bake a cake.’

“When visiting her at Ahus in the psych ward,” he continued, “the staff would open the front door a few inches and say to us, ‘I can ask her if she wants to talk to you.’ Normally the meeting was in the doorway or in the hallway outside. When she was at Sunnaas, we, her parents, were always invited to staff meetings, making plans, how we could help and so on. That never happened in the psych ward. We had the feeling that the staff at the psych ward looked at us as the enemy, instead of as a resource.“