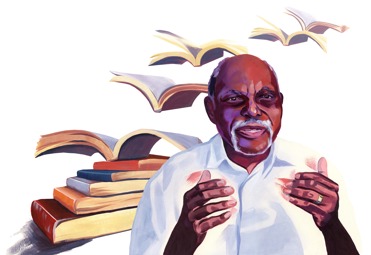

Vol. 47, Issue 2 ‣ profile

Community Leader Cecil Murray

In the late 1950s, as a jet fighter raced down the runway at Oxnard Air Force Base in California, a tire blew just before takeoff. The two-seater plane careened out of control and crashed to a stop, fires erupting. The flight’s navigator managed to crawl out onto the wing through a small hole between the fuselage and the cockpit cover, barely escaping the inferno that, just then, enveloped the aircraft.

Just before he jumped down to safety, the navigator spotted his pilot down the wing, his body engulfed in flames. The navigator rushed to the pilot’s aid, throwing him to the ground and rolling him—over and over and over again—until the fire was out, in the process severely burning his own hands.

The pilot, with burns on 90 percent of his body, was flown to a special burn unit in San Antonio, Texas. There he made an urgent request to have Cecil “Chip” Murray, the navigator, brought to his bedside—before he died, he had something to tell his rescuer. “I didn’t abandon you,” the pilot whispered. “I was coming to get you when I slipped and fell in the fire.”

Murray, a black man born in Lakeland, Florida, had personally experienced the effects of racial bigotry, hatred and violence. The pilot was a white man from South Carolina; his last words to Murray: “I love you.”

Profoundly moved, Chip Murray knew from that moment he was not living for himself alone, but to help others. (To this day, Murray says, he keeps in touch with the pilot’s brother.)

Decorated by the Air Force for heroism, after he left the military Murray would continue his dedication to service. He became a First African Methodist Episcopal minister, serving that faith in several cities before arriving in Los Angeles in 1977.

As senior pastor of L.A.’s First African Methodist Episcopal Church, he built a congregation of 250 into one of the nation’s largest, 18,000 strong. He also served as a mediator resolving racial conflicts and led dozens of task forces, tackling such issues as homelessness, healthcare, substance abuse, jobs, education, housing, and HIV/AIDS awareness.

Murray soon became one of the most recognized ministers and community leaders in Greater Los Angeles.

Presidential candidate Bill Clinton and President George W. Bush are among the many national figures who paid visits to Murray’s church and addressed his congregation.

After 27 years, Murray left his position leading the L.A. First AME Church, and took a faculty position at the University of Southern California, where he holds the John R. Tansey Chair of Christian Ethics in the School of Religion. He was also named a senior fellow of USC’s Center for Religion and Civic Culture.

He also heads the Cecil Murray Center for Community Engagement, which develops projects connecting church communities in L.A. neighborhoods with the resources of the university.

“In the past three years, we have reached 700 churches and their leadership, pastors and lay leaders,” Murray says.

Murray’s eponymous Center runs church-community engagement programs that foster economic self-sufficiency for low income communities; offers training to nonprofit agencies and businesses in leadership, governance and administration; facilitates faith-based community development; and advocates for public policy supporting neighborhood revitalization. “We take pastors and lay leaders and train them in civic initiatives, reaching beyond the walls of the church, finding a way to say ‘yes’ for those who are in need,” Murray says.

Murray also works on the Passing the Mantle Project, which trains clergy from African-American churches throughout California in effective development and organizing strategy.

To bring the many and diverse populations of Los Angeles together on common religious ground, Murray keeps his programs responding to dramatic demographic shifts. With some traditionally black neighborhoods now two-thirds Hispanic, and a Pew study reporting increasing numbers of Hispanics turning to Protestantism, Murray launched the Faith Leaders Institute which trains theological leaders to span ethnic divides.

The Cecil Murray Center also conducts, in collaboration with the USC Schools of Law, Business and Social Work, a 12-week community-outreach training course for church leaders. “Participants then go back to their church to undertake the project of community uplift,” Murray explains. “Some will choose to work with the homeless; some will choose to work in foster care. Some will choose to work with those being released from prison so the recidivism rate can be reduced.”

Murray has worked with leaders and members of the Church of Scientology on a wide range of community betterment initiatives for decades, including programs to boost learning skills and eradicate illiteracy, drug prevention efforts, and campaigns to curb crime and violence.

Bob Adams, a vice president of the Church of Scientology International, leads interfaith coordination efforts with Murray. “He is a man of courage and integrity who respects all religions and people of all faiths.”

Murray describes his work as “making differences in underserved communities, being that rising tide that lifts all vessels.”

Indeed, to be a positive change agent has long been the goal and the message of Cecil Murray, a man of indomitable courage who has dedicated his life to social betterment by constructive means. “Soul force is greater than sword force,” he says.